Individually, these observations are outliers. Collectively, they paint a picture of a changing planet.

The Local Environmental Observer Network, or LEO Network, aggregates these types of observations into a searchable, clickable database. The project is a collaboration between Alaska Pacific University (APU) and the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC). The network has 4,110 members submitting observations from around the world, but it’s housed right here in Anchorage.

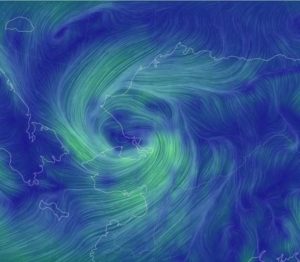

Residents of Golovin reported an extremely windy day in the bay. LEO Network experts provided wind maps to match.

LEO Network’s website features a map of the globe with pins pointing to news stories and daily observations from group members. All submissions are vetted by subject experts and include everything from news stories about coastal erosion to Facebook posts about a sudden worm infestation. The Golovin winds, for example, were reported by residents of the primarily Iñupiat village who shared their experience and photos with the network.

Local observers are especially important to the project, explained Chyna Perez-Williams, an environmental public health student at APU and an editor for LEO Network.

“It’s a bridge between scientists and non-scientists,” she said of the network. “We believe at LEO that the local observer, the person who has lived on their land for generations, knows the most about it.” Observations can inform Outside researchers about local conditions, she added, “and that power should be in the hands of local observers.”

Ultimately, these collective observations connect the dots between climate change and community health, explained Mike Brubaker, who directs the LEO Network. The program is part of APU’s Center for Climate and Health, an affiliate of ANTHC. LEO observations demonstrate how climate change can impact things like rural infrastructure, food security, water supplies, and more.

Residents of Kotzebue submitted summer storm surges this July.

As editor, Perez-Williams is also focused on expanding the network of submitters. She aims to visit APU courses this year to share the network with classmates. APU students are an ideal avenue for expanding LEO observations, she said, because they’re passionate about the environment and have their own networks to connect. Many students have families in rural Alaska or in the Lower 48; more observations from more locations will lead to more data. “Anybody who lives anywhere can be a member,” she explained.

So far, there are 4,800 observations recorded in the LEO Network. Each dot on the LEO map exists because a member decided it was worth sharing.

“What’s really important for me is having people feel like they have a voice in science,” Perez-Williams said of the project’s collaborative design. “Ultimately, we’re the ones who have to live in our environment, and sometimes we have to fight for our rights to healthy air, healthy food, and healthy water.

“The more information we have about our environment and how it affects our health and wellbeing, the more power we have to make any necessary changes,” she said.

Click here to explore the LEO Network’s map of observations.

Click here to register and submit your own observations.

For more information about the LEO Network or the Center for Climate and Health, contact Mike Brubaker mbrubaker@alaskapacific.edu