Thanks to its orbiting satellites, NASA can record where the earth is growing greener or browner over time. But when each pixel from space is roughly two and a half football fields on earth, what’s the biological meaning of a shade of green?

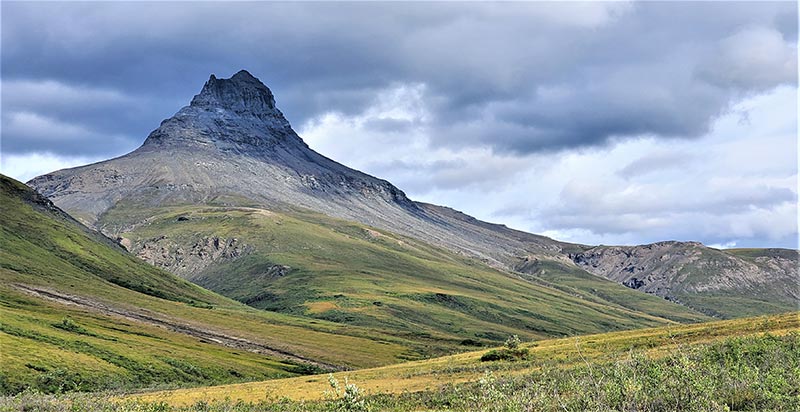

Professor Roman Dial led a month-long research trip through the Brooks Range, accompanied by six environmental science and outdoor studies students (Photo by Toshio Matsuoka).

To answer that question, a research team from Alaska Pacific University (APU)– six students and one professor – headed to the Brooks Range for a month-long trek, collecting observations on the ground to compare against NASA’s imagery from space. The goal was to cover as much ground as possible, hiking over low mountain passes, rafting downstream to the next river valley, crunching over late-summer snowpack, and traveling light. The research gear was especially streamlined; all they needed to record observations was a smart phone, a battery pack, and – if the weather cleared – a solar charger.

“It’s not just hiking. It’s not just recreating, it has a focus,” APU Professor Roman Dial said of their data-collecting method, which the group called “pixel-walking.” During a four-week expedition, Dial’s students collected 3,000 data points along a 375-mile route to compare against satellite imagery.

Students recorded 3,000 vegetation data points on their iPhones, to compare later against NASA satellite imagery (Photo by Toshio Matsuoka).

For the past 20 years, NASA has recorded light reflecting off the earth to determine vegetation changes on the ground. Visible light is absorbed by plants for photosynthesis. The more light that’s absorbed, the denser the vegetation, and the “greener” the pixel will appear on satellite imagery (where “greenness” is really a ratio between red light that’s absorbed for photosynthesis and infrared that’s reflected). Generally, the Brooks Range has gotten greener over the past two decades.

There are two key reasons why an area could change color over time: greener plants like shrubs may overtake layers of lichen and moss, longer growing seasons could expand the leaf coverage, or both could occur simultaneously. NASA can’t know for sure unless someone on the ground goes to verify. That’s where APU comes in.

Starting each morning, Roman would lead his team into the bush, charting the course while four students trailed behind, recording significant vegetation changes. At each data point, students would note the two tallest plant layers – evergreens, deciduous trees, shrubs, mosses, etc.– to determine later if one might be dominating another and changing the color of the pixel. By expanding that information across 3,000 data points, the team could start to determine natural patterns of vegetation growth and theorize the effect of recent changes in climate.

(Photo by Julie Ditto)

The research called for condensing a large area of diverse vegetation to compare against just one NASA pixel. “I really realized how much energy it took to collect data,” said Julia Ditto, an environmental science major. On the trip, students hiked and hypothesized 10 to 12 hours of the day, making judgment calls of natural progression at each stop. “I can hike up this pass, I can walk all these miles, but to record data while doing it was mentally taxing,” she noted.

The team prepared throughout the summer on group hikes in the Chugach Mountains near Anchorage. They experimented with different apps and tasks to determine the best method for data collection. They weren’t just learning the pixel-walking method, but creating it.

“I had this perception going in that there’s this thing we’ll be doing, and I just have to get the hang of that thing,” Toshio Matsuoka, an environmental public health major, said of pixel-walking. Instead, they built the technique through trial, error, and adaptation. “Experiencing the whole methodology of science and seeing it develop from the ground up was a pretty amazing thing to watch.”

The team travelled 375 miles by hiking and packrafting through the Brooks Range (Photo by Julia Ditto).

In between test hikes in the Chugach, the students also learned to packraft, prepared food and supplies, and developed the protocols for the trip. That level of involvement helps students be invested in the research, said Roman.

“I feel like APU is a perfect place to do this,” he said. “It’s an experience that’s hard to beat, especially if you’re an outdoor-oriented student and interested in the effects of climate change.”

Students received support from a variety of sources – including Josh Lewis and Vic Becwar-Lewis, BLaST research grants from the University of Alaska Fairbanks (funded by the National Institute of Health’s Diversity Program Consortium) and summer scholarships from the Garden Club of America. Several students received course credit for their contributions, while others collected information for their senior projects. Russell Wong, an outdoor studies major graduating this fall, is writing a methodology for the pixel-walking process so other researchers can follow their footsteps of lightweight wilderness travel and simplified data collection.

“These Brooks Range expeditions feel like they’ve been a culmination of my college education,” said Russell, who joined Roman last summer for a tree line research project in the North. “Being able to go to the Brooks Range to learn more and use my skills in the outdoors and include this science component is more than I could have ever dreamed.”

After a day of data collection, the team would find a water source and set up tents for the night. They’d cook shared meals over camp stoves and dry their clothes by the fire, maybe plucking a few songs on the group ukulele (a lightweight instrument for a fast trek through the tundra).

After a month of focused effort, the team returned to Anchorage to start the school year and process their data. But routines from the trip have lingered.

“I’ve never paid so much attention to what I’m walking through,” Toshio said. “It’s hard to go back to just walking.”