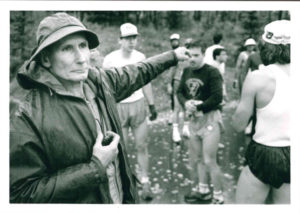

Organized to appeal to runners of all abilities with the lightning, farm, and munchkin division, the Tuesday Night Races are about more than just speed. It’s a way to explore new area trails (participants don’t know the course until moments before). It’s a way to get active, at your own pace. And it’s a community builder, making all who run a part of a larger team.

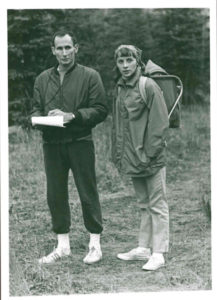

To kick off the 50th season, the Races will return to where they started: APU. But before runners and walkers hit the trails, they’ll get to hear a few words from the man who started the Races that would make all of Anchorage part of one big team: Jim Mahaffey.

The start of a lasting tradition

Bill Spencer, one of Mahaffey’s athletes in his final year of coaching, said the runs were “the most dreaded or anticipated workout of the week” for the skiers.

At the time, there was little opportunity for people in Anchorage to run competitively.

“Not that there were many runners,” Mahaffey said. “People that were running were either in training for something or were crazy. But I opened up the races to anyone who wanted to run and soon we had local doctors, lawyers, and business people racing against our skiers.”

After the school restructured, the logistics of organizing the growing event were transitioned to the Municipality of Anchorage Parks and Recreation Department, where the responsibility remains.

Bradley Cooke, the current Outdoor Recreation Superintendent for Anchorage’s Parks and Recreation Department, said the races have become an important part of the fabric of Anchorage, reinforcing how Alaskans choose to get the most out of each season.

“It’s provided an outlet as school and fall set in for families to come together once a week to inspire each other and build their community,” Cooke said. “Getting these families to run these races where munchkins get to race alongside the elite runners has also planted the seed for a long life of healthy and outdoor pursuits.”

A history of a man built by athletics

Mahaffey retired from APU in 1992, where he built the foundation for what is now the Outdoor Studies program; his first outdoor studies block course included a week-long traverse of the Talkeetna Mountains and another week of canoeing on the Kenai Peninsula. He grew the ski program from a club sport to one that turned six athletes into Olympians and became the nation’s first women’s varsity cross-country team, all while establishing the University’s trail system. While the goal in all his endeavors was to help the university attract students and athletes, his drive was his devotion to sport and the comradery that comes through being a part of a team.

Growing up in Pennsylvania, a few hours north of Philadelphia, Mahaffey received his first pair of skis at age five. They were a simple set: wood, with just a leather toe strap. And even though nobody formally taught him the sport, it clicked for him in ways that football and basketball didn’t.

“Even just plowing down the hill, not knowing anything about turning, I just liked it,” Mahaffey said.

After high school, Mahaffey joined the Air Force and was sent to Elmendorf Air Force Base in 1950. It was there he got his first taste of Alaska and where he really learned how to ski. At the time, the military had a robust athletics program with local coaches and competitions against the six or seven other teams across the state.

“My team won every race for three years in a row,” Mahaffey said as he cracked a sly grin. “We were good enough that we were going to compete in the Lower 48, but the Korean War screwed that up.”

After finishing up his contract with the military, Mahaffey headed to Western State College in Gunnison, Colorado. During the school year he studied teaching (he received both an undergraduate and master’s degree in education from Western) and competed in downhill, slalom, jumping, and cross-country skiing – in 1956, he was a member of the team that took first at the NCAA cross-country championship. During the summer, he found his way back to Alaska to work as a commercial fisherman.

Alaska would continue to call him home. After graduation, Mahaffey took various jobs involving skiing, before being offered a role University of Alaska Fairbanks as an assistant professor and ski coach.

“I liked working up there, but the snow they get offered too many limitations,” Mahaffey said.

Mahaffey explained that when you ski race, you need a hard course. The snow in Fairbanks was so cold and dry that after a few athletes went down the course, the tracks would be knee deep.

“I also missed the bigger mountains,” Mahaffey said. “Not just for skiing, but for recreational activities.”

So he came to AMU.

Blazing new trails

In his time as coach here, Mahaffey rebuilt the team from the ground up, forging new trails, training athletes to the highest caliber, and stretching his budget to allow his team to travel to showcase their dominance all over the country.

“Jim was quiet, intense, demanded commitment and didn’t take excuses lightly,” Spencer remembered. “If you missed a workout, you had to stand up in front of the team and explain why you thought you had something more pressing to do than be there working out with everyone else who had sacrificed to be there.”

When asked what some of his favorite memories from his tenure at AMU were, Mahaffey said, in all seriousness, “Oh, it’s all my favorite memories.”

“I had a lot of good kids over the years, some of whom I’m still really close with,” Mahaffey said.

Spencer echoed that sentiment, saying, “Jim followed us all as we left his program and went on to other endeavors, so we all still count him as a friend. He demanded hard work and loyalty, and the man had an integrity and character not often found in small school coaches.”

Earlier this year when Mahaffey was awarded the prestigious Joe Floyd Award (an accolade given to someone who has made significant and lasting contributions to Alaska through sports) two of his former skiers, who now live in Montana and Oregon, flew up to show their support. Others he still exchanges Christmas cards with or meets up with for coffee.

“You sure didn’t get rich working for AMU — I didn’t even get paid for coaching,” Mahaffey said. “That wasn’t the reward. At the time, it was having success and then in later years, having kids come up and say how being on my team impacted them, that was the reward.”