Written by Dale Lehman, Ph.D., Director of MBA Programs and Professor of Economics at APU

You may have seen recent news headlines such as “Obesity Rate for Young Children Plummets 43% in a Decade” (New York Times, February 25, 2014). This story, picked up by virtually all American newspapers, originated with the publication of a research paper by authors at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.* The press release was titled “New CDC data show encouraging development in obesity rates among 2 to 5 year olds.” The cited 43% decline was from 2003-04 (obesity rate of nearly 14%) to 2011-12 (obesity rate just over 8%). Perhaps more startling was the decline from over 12% in 2009-10 to 8% in 2011-12; a decline of approximately 33% in just 2 years!

* C.L. Ogden, M.D. Carroll, B.K. Kit, and K.M. Flegal, Prevalence of Childhood and Adult Obesity in the United States, 2011-12, Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 311, Number 8, pages 806-814.

Since that publication, the blogs have been bustling with criticisms, disbelief, and accusations of political motivations. Readers who looked at the paper might have been surprised at the fairly modest conclusions: “Overall, there have been no significant changes in obesity prevalence in youth or adults between 2003-2004 and 2011-2012.” The paper did, in fact, find a statistically significant decline in obesity among 2-5 year olds; a finding that made it to the press release but not to the paper’s conclusions. What is the real story?

Among the criticisms that have thus far emerged (and which I share) are the following:

- The reduction in obesity was one of only 2 significant changes in obesity over that decade. Though statistically significant on its own, it may be a spurious result given that the paper did a number of other comparisons. This is a somewhat subtle statistical point, but valid, and in fact recognized by the authors of the paper: “Because these age subgroup analyses and tests for significance did not adjust for multiple comparisons, these results should be interpreted with caution.”

- The contrast between the paper’s conclusions and the CDC press release raises the possibility of political motivations, since the current Administration has made child obesity a major concern.

- The sudden and large drop in obesity (particularly in the last 2 year period) looks suspicious and strains credibility.

I will not elaborate on these further as they are well represented in numerous blogs and comments. Instead, I have some original contributions to the debate, starting with my attempts to replicate the analysis in the study.

When I download the data, I find 916 children aged 2-5 years old in the 2011-12 data with obesity data for 883 of these individuals. The published study claims there are 871 children aged 2-5 with obesity data. I cannot account for the difference but it disturbs me that there is not an exact match – since I download the data from the same National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The numbers are close, as is the obesity rate – I find 8.37% and they report 8.4%.

The important finding is the dramatic fall in the obesity rate: I show it dropping from 12.34% in 2009-10 to 8.37% in 2011-12: this is close to the drop reported in the study from 12.1% to 8.4%. This is a remarkable and encouraging finding – if it is reliable.

There are reasons to doubt the validity of the comparison, however. There were two important changes made to the national survey starting in 2011-12. In prior surveys, the obesity status was obtained by comparing the BMI (Body Mass Index) to cutoffs used by the CDC (the 95th percentile on the CDC growth charts is used as the threshold for obesity) and this comparison had to be done manually. Beginning with the 2011-12 survey, “a new variable, BMDBMIC, was created as part of the Body Measures Exam file to provide analysts pre-computed BMI categories for children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years at examination.” In other words, the CDC did the work of converting the BMI data into obesity categories. At the same time, they stopped reporting the age of children and adolescents in months, only showing their age in years. This is important because the CDC growth charts are based on the age in months. Thus, there is no way for me to go back and verify their calculations of the obesity rates.

* They do explain why this data is no longer publicly provided: “Due to increasing concerns about potential disclosure risks, information on age in months at screening and at examination for participants in other age groups are no longer included in the public release file but are available through the NCHS Research Data Center (RDC).” In theory, I might be able to do this, but it is a lengthy and complex procedure to gain access to that data.

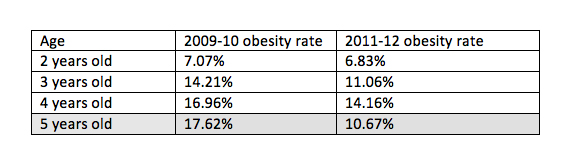

An important observation is that the drop in obesity in the 2-5 year old age group is mostly concentrated in the 5 year olds, as shown in the table below:

While all ages show some reduction in obesity rates, it is the 5 year olds that really drive the results – and the reduction in obesity among 5 year olds is truly extraordinary.* So, I chose to focus my attention on these 5 year old children: there are 371 children (193 from 2009-10 and 179 for 2011-12), 53 of whom were obese. The 2011-12 group weighs less and has lower BMIs – that is why there is less obesity. But, strangely, they are also shorter, and have smaller arm and waist circumferences. This makes me wonder whether they might, in fact, be younger.

* To gauge how extraordinary it is, the probability that only 19 (10.67%) of these children would be obese if the true obesity rate had not changed, is only 0.5%.

How could 5 year olds in 2011 be younger than 5 year olds in 2009, you might wonder. There are two ways this can happen. First, the 2011 group might be closer to 5 years old while the 2009 group might be closer 6: but I can’t determine this without the age data in months, which is not available for 2011-12. Second, it is possible that the pre-computed obesity categories identified children between 4.5 and 5.5 years of age as 5 years old. In prior surveys, 5 year olds were between 5 years and 5 years and 11 months of age. This would be an error – to deviate from the past practices – but people do make errors and I am unable to check this because the age in month data is no longer reported.

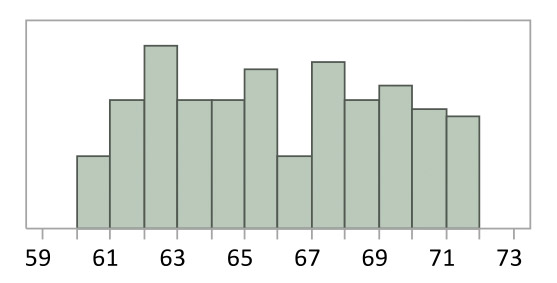

Figure 1 shows the age distribution for the 5 year olds in 2009:

So, the 2009-10 cohort is relatively evenly spread out between the ages of 5 and 6. It is possible that the 2011-12 group is more concentrated on the 60-65 month side, but again I cannot tell. Five year olds could be getting younger as well as less obese!

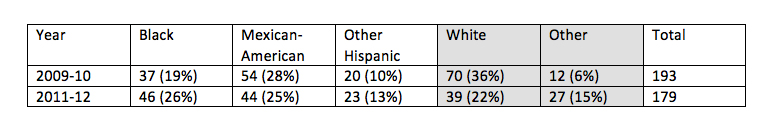

More seriously, there are significant differences between the 2009 and 2011 children. The ethnicity breakdown is shown in the next table:

I have marked the significant shifts in the survey participants. Given the small numbers of individuals and the sizable shifts in ethnicity, it is hard to view the obesity rates between 2009 and 2011 as an apples-to-apples comparison.* Not only are children getting less obese, they are becoming more diverse!

* I would also note that the CDC growth charts identify obesity solely on the basis of age – there are no separate tables for different ethnic groups. This is disturbing, especially when the ethic makeups vary this much across survey years.

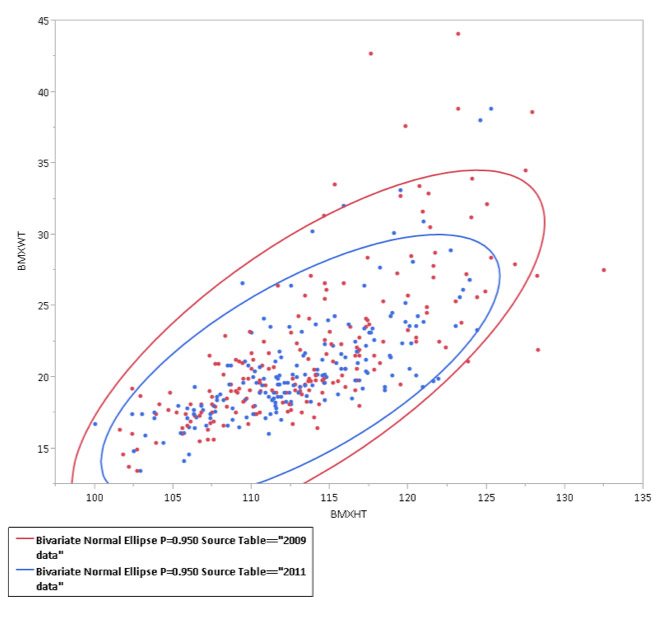

It is also interesting to compare the 2009 and 2011 groups with respect to their heights and weights. Figure 2 shows these individuals (red for 2009 and blue for 2011), along with density ellipses (drawn around 95% of the individuals in each group):

It is evident that the 2011 cohort has narrower ranges of both heights and weights. Not only are children getting lighter, but they seem to be getting shorter!

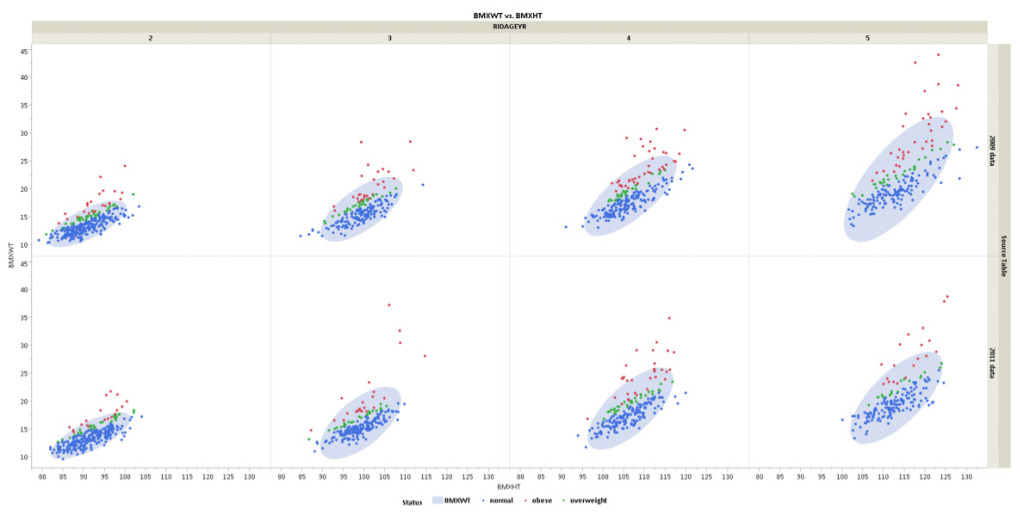

The dramatic change for 5 year olds is even more evident in Figure 3, showing the heights and weights by age for 2009 and 2011 with colors marking obese, overweight, and normal (everybody else) children:

The red points show the obese children and the shaded ellipses contain 95% of the children in each age and year group. The increased obesity among the 5 year olds is evident – but also evident is the larger region of heavier and shorter children in 2009 compared with 2011. The shift in children sizes is not so evident in ages 2-4, but only age 5 shows the stretching in both the vertical (weight) and horizontal (height) dimensions for 2009 compared with 2011. Therefore the results in the headlines (dramatic drop in obese children) appear to be driven predominantly by the 5 year old group between 2009 and 2011 and this one group of children seems anomalously incomparable between the two years.

The moral of my story

Obesity is an important public health issue. If, in fact, young children are becoming less obese, that is very good news. It matters to know whether this is a valid finding – it might mean we are doing some things right (and should do more of those things) or it could mean that we are not successfully combatting obesity (and we need to try different approaches). The CDC study is vital information and was careful in its conclusions and fairly thorough in its analyses. It falls short in several critical respects, however:

- It failed to inform readers of the significant changes in the 2011-12 survey data from previous surveys. This is doubly important since most of the decline in obesity was only observed in this most recent survey.

- It failed to provide enough detail to permit replication of its results. The raw data does not match what can be downloaded, and the authors omit specifics that would be necessary in order to replicate.

- It did not adequately explain where the largest changes in obesity occurred (e.g., it provides results for the 2-5 year old age group when almost all of the reduction was with the 5 year olds), nor did it highlight the significant differences between the composition of the cohorts in 2009-10 and 2011-12.

If we are to take replication of results seriously, and we should, then more extensive provision of data and better documentation will be required. Open access to data is a major policy issue (particularly in medicine) and some progress is being made. However, the depth of the problem is not fully appreciated. This is a case where the data source is publicly available – and replication is still not possible.