The river and lake system near the Alaska Native village of Nanwalek has long welcomed the red salmon that return en masse each summer.

But with dwindling numbers of their preferred subsistence food, the village also welcomed some fresh fish to help develop a salmon monitoring program for the community: APU’s FAST Lab and Alaska Department of Fish and Game collaborators.

For a few days in late May, Professors Brad Harris and Nathan Wolf and graduate students Kelsey Bockelman, Anita Kroska, Brianna King and Karli Tyance helped conduct research that will aid the village in determining why they’ve seen fewer salmon returns.

The group tested numerous theories, all the while getting the community involved in the efforts.

“It wouldn’t do for us to come in, find a solution and leave,” Harris said. “This was about empowering the students and the villagers with the skills to do it again later. The point of us being there is for everybody to learn something.”

The graduate students who helped with the surveying were part of Harris’ Ichthyology (the study of fish) course.

Traditionally, ichthyology classes involve hours clocked in lectures and memorizing hierarchies of what separates the fish based on their traits. And sure, this class does that, too. But they also spent two weeks doing practical learning in the field.

“Students learn best when they’re out there doing it,” Harris said. “The opportunities we had for field work are equal to a lifetime of education.”

The study of fish

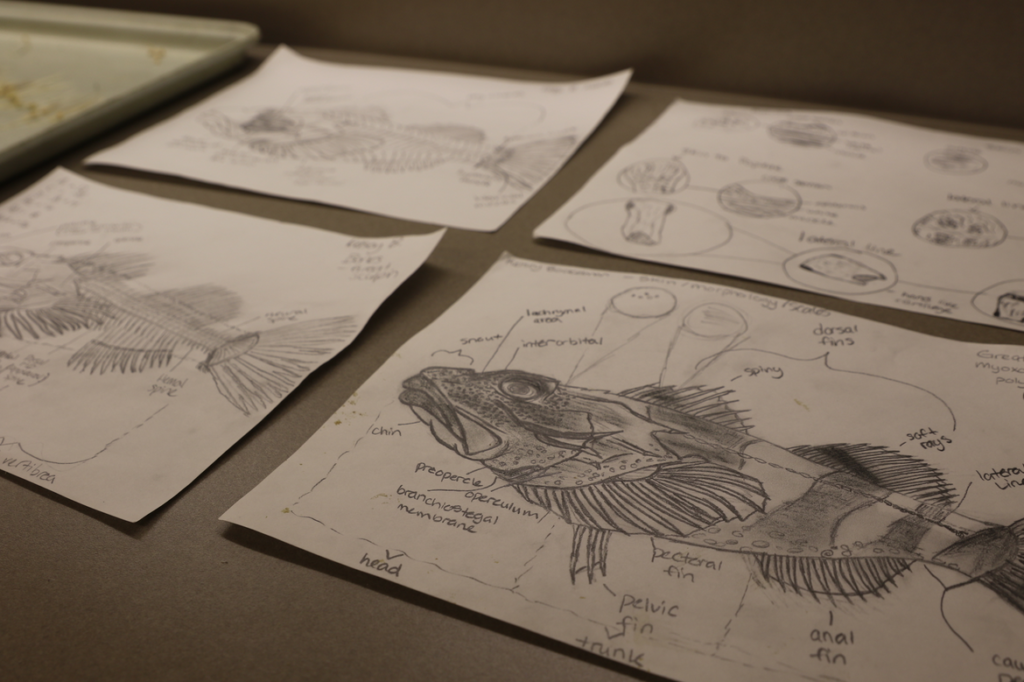

At the macro level, Harris’ ichthyology course focuses on fish and how their various forms aid in how they function. In the first week, students identified fish Harris had caught during the prior year and then chose their own to dissect and draw.

“You get a stronger understanding of that fish as an organism this way,” Harris explained. “That’s helpful because most of the students in the class are on career paths that will deal with whole populations of fish ecosystems. When you’re thinking about how global warming is affecting fish as a whole you forget about individual entities. To develop good management practices and answer important scientific questions, you have to understand how the fish work at a base level.”

Two of the fish chosen for dissection were a sculpin and a halibut. Though they both live at the bottom of the ocean and eat the same organisms, their shapes are wildly different. The former has a massive head and small tail, whereas the latter is long and flat.

“Breaking them down allows the students to understand better how the two have evolved to make a living and will later help them understand the best practices for working with them,” Harris explained.

For the first week of the course the students completed numerous drawings of their fish: first the fish as a whole, then just the muscles, then, after the skeletons had been cleaned by flesh-eating beetles, they drew the bones.

Harris explained that seeing the fish in all forms and understanding components like musculature, locomotion, and dietetics of salmon is essential for working with them.

“Let’s say you need to decide on the placement of a salmon weir,” Harris said. “You don’t want to stress them out or kill them, but you also want to make sure they go through the counter and not around it. Knowing how they function allows you to make informed decisions about where to put the weir so that it’ll be an effective tool for counting.”

Working with the fish, Harris said, would give the students the practical knowledge they’d need for field projects.

Field Notes

For the two weeks in the field, the class predominantly worked in or around Homer.

They assisted the Department of Fish and Game with a razor clam survey, helped build the salmon counting weirs on the Anchor and Ninilchik Rivers that will be used to determine if a sustainable amount of salmon were making it up river to spawn, stocked a lagoon with silver salmon, and traveled to Nanwalek, the Alaska Native village on the other side of the bay to help the community run tests.

“It was a busy couple of weeks,” Kroska said. “The course definitely wore out our bodies and our brains.”

While each of the students said they enjoyed the emphasis on all of the accrued fish biology skills, the highlight was working with the Nanwalek community.

“Everybody was so welcoming,” King said. “And it’s really rewarding to be doing projects of value, instead of just sitting in a class.”

Using information they’d learned about salmon, the group ran a myriad of tests. From water quality and environmental samples to taking pictures with a drone and mapping the whole watershed.

The students explained there are numerous factors that could have led to the decline, so finding the answer will take time. It could be that the lake productivity (the carcasses of deceased fish feed the plankton that juvenile salmon eat) is hampered by a big run-off of melted snow flushing the nutrients down the river before the eggs hatch, resulting in no food for the new salmon. Or maybe it’s a problem with the water. Or perhaps not enough salmon are coming back up the river. Or it could be overfishing.

Tyance, an AnishinaabeKwe from Gull Bay First Nation, has an interest in exploring traditional ecological Indigenous knowledge of the past and current salmon fishery management and will be returning to Nanwalek throughout her graduate work to continue to help the community find solutions and better understand their salmon.

“It’s really exciting to be able to use the skills and knowledge we’ve learned in class towards something bigger,” Tyance said. “I’m glad I’m going to have the opportunity to continue working with these people.”

Kroska echoed that sentiment, saying, “Doing projects like this made me feel like jobs are within reach. And they’re always stoked to work with us, too.”